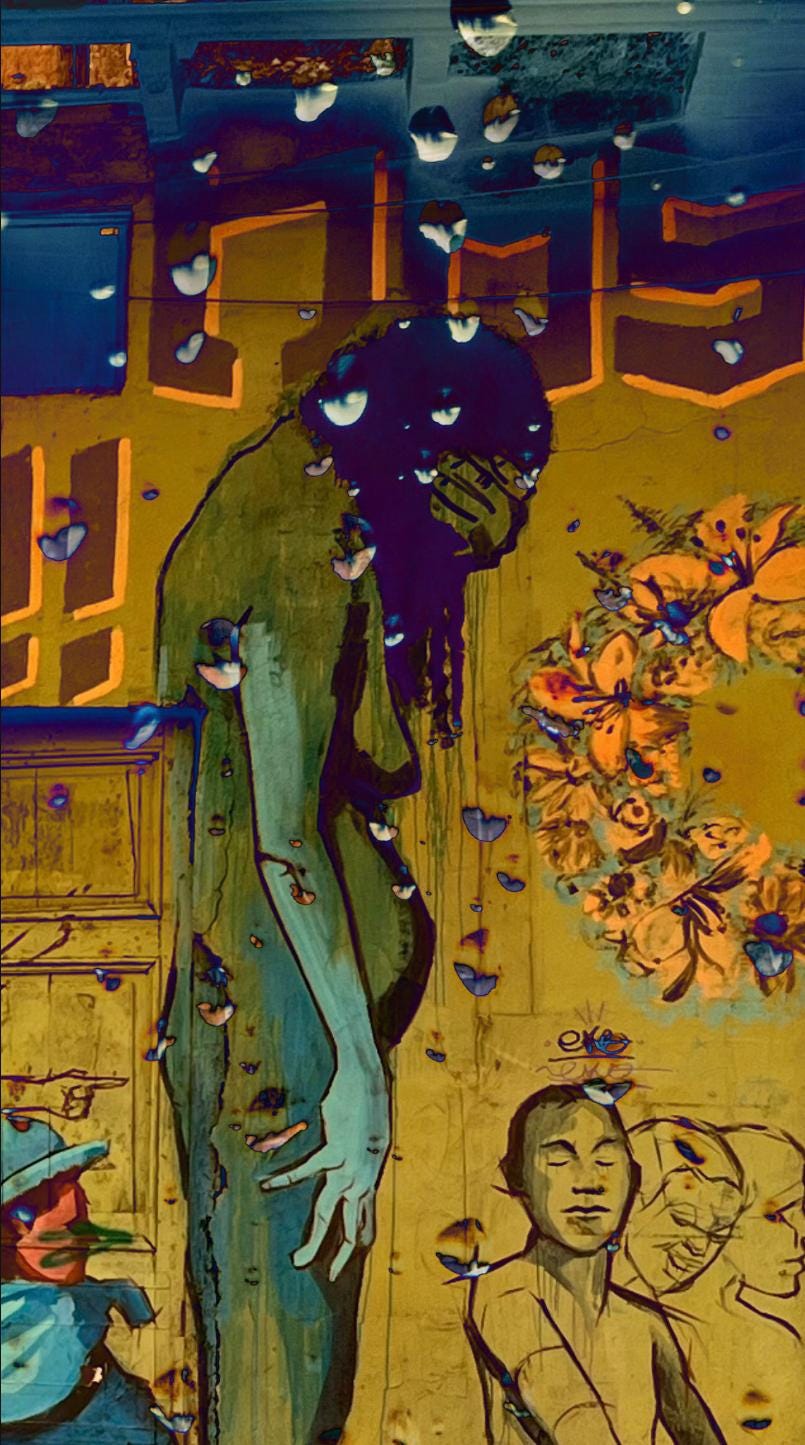

You are in the dream. A house glows in the darkness of a vast wood. Pushing the front door open, you enter. The interior is grand, a balcony hovering over a sprawling living space. You wander through lush rooms until at last, you see him. The man with all the answers, all the power—his house—and you want to impress him. But you realize you’re still wearing your shoes and when you go to take them off—in the middle of a creamy expanse of carpet in the warm wood paneled hall—you see your sandals are tied on with dirty rags. Unwinding the strips of fabric, bales of flowers appear under your feet, stems and leaves threaded into the straps. Do you unbind the bouquets—unstrap your sandals and step out of bundles of peonies and bluebells, rosemary and lilies—for him? Do you worry about the fallen flowers on the carpet in his enormous house? Of course you do. You want to impress him. You want him to love you, and your feet wrapped in dirty rags, keeping the flowers close, softening your steps. So, you unravel your feet for him—loosen the flowers—in the evening after his guests are already in bed—as a gift. They expand, largely unbruised. A hundred kinds of blooms. And you stand there in the living room intently watching for his reaction to your secret heap of flowers. He has a sort of gentle pity on his face, disinterest. A hint of annoyance. You are confused. But look at all these flowers? They are magnificent and unbroken, uncrushed by your long, harrowing journey

—and your mind goes to the boy from kindergarten, your friend who was kind and always dirty, and how once, in the cafeteria he was putting ketchup on his hot dog bun and the dog rolled out and off the table, onto the floor, and his face crushed then went feral then slightly defiant. You offered your own hot dog to him immediately, to share or just for him to have, but he couldn’t take it from your mouth for his own fumble. He crawled under the table to retrieve his dog, rolled the tube of meat between his grubby hands to ‘get the dust off.’ There was a lot of dust. He blew on it, puffing his cheeks, huffing repeatedly, attempting to blow the dirt away. He did this to prove he could be relied upon to solve his own problems. He did this to hide that he needed to eat that hot dog, that there wouldn’t be anything at home later, that there was no money to buy another. You felt such sorrow for him, for how he must have lived. How even at five, he knew desperation and impossible choices. And you, also five, judged him then, felt pity and disgust, and wanted to get away from him. These are the flowers you carry around. Peonies for your sorrowful understanding that he didn’t feel he could ask the lunch lady for another. Irises for your wide, horrified eyes when he bit into it. Carnations for the shame that changed your mind about your plan to invite him to your house. Roses for how you still loved him through all of it. Your poor friend. You didn’t know what to say to preserve his dignity, or how to help.

—another boy, (also poor, also dirty,) who lived in a decaying trailer, smelled strongly of unwashed mildewed fabric and engine grease, who approached you hesitantly at the middle school dance, shaking and terrified, and asked you to dance. You said no—you all hot social shame and self-disgust—and he ran away crying. He was just a boy—a gentle and kind one. You sat near each other in writing class. His hands were always filthy, and he raised pigeons. Brought one into class once for show-and-tell in a Havahart trap. He cradled his pigeon gently, like a living gem. He glowed with love. But the rest of the class over-poured with disgust and revulsion and showed their teeth, distancing themselves—the flowers strapped to his feet were ridiculed as gross and impoverished. His birds, your flowers. But it was more than that. He asked you to dance because you were kind to him, saw him as whole, saw him for himself. You are strapped with bouquets, ligatures of grimy rags binding hot dogs rolled between your fingers, lashed with iridescent gray bird wings, defiantly wearing cheap clothes even now, intermittently smelling of armpit, sweat, grease. You do not adorn your body and disdain dressing up—markers of class and success elicit secret derision inside of you. Disinterest. Revulsion. Peel back these layers with the flowers. There’s something burning here.

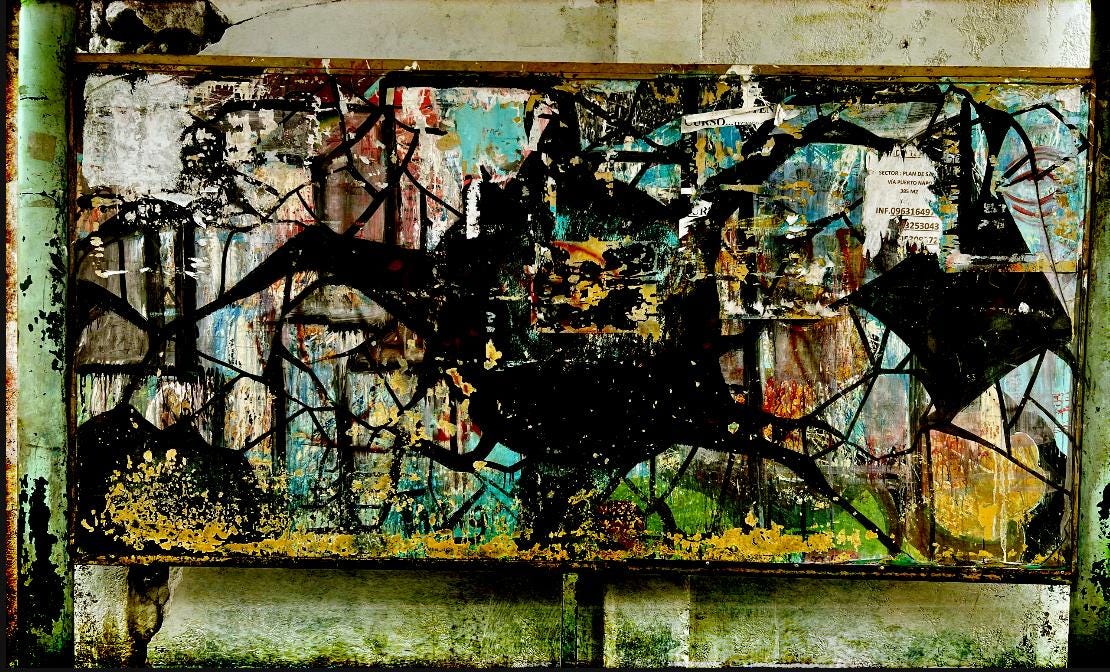

You are gross and poor. He was gross and poor. You can cut all the flowers but you cannot stop spring from coming. You can strap them to your hands and feet to splay out on some strange man’s living room rug in an attempt to impress or hide your hunger in the hopes he will love you, but you cannot stop the shame from coursing through you. For shame, you unbound your feet. For shame, you witnessed hunger and did not offer help. For shame, you were offered flowers, bruised and strange as they were, and it was pity and revulsion that grew up inside you. What inside you has been stepped on and gone unwashed by gentle hands? What else inside you has been crushed and bound, ignored and starved?

See this shame. See how it continues to flower even under pressure. How the light glints off the nectar in the dark centers. May every fallen petal be a bite taken, each teardrop-shaped reflection a mirror taking wing. I am blowing the dust off. I am asking it dance.

You are a teacher of turning the gaze in and looking for the part that needs to grow or be pruned. xx